- Home

- Ginny Gilder

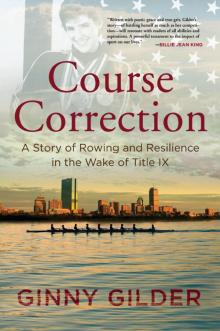

Course Correction Page 27

Course Correction Read online

Page 27

The heart wants what the heart wants. Long suppressed, kept corralled in a safe and sensible harbor, mine finally broke free and grabbed the rudder to steer me into wild waters. There was no turning back.

19

“My husband and I are struggling.” I couldn’t solve this problem by myself. I sought counsel from an expert, a therapist who specialized in children. Maybe she could terrify me back into behaving with her stories of kids ruined by divorce.

“Tell me what’s happening.”

Deep breath, hands clenched together, bracing for the lecture about selfishness and responsibility, I said, “I’ve fallen in love with someone else. A woman.”

“Where did you meet her? Are you going to live together here? Seattle is a great place for gay couples.”

“What? I haven’t even decided whether I should leave my marriage. I just don’t know if I can do that to my children.”

“You’d stay in an unhappy marriage for your kids?”

This was not the conversation I had anticipated.

“I lived through my parents’ divorce … barely. I don’t want to do that to my kids.”

“Divorce isn’t usually the problem. It’s the parents’ reactions that cause the most trouble.”

Old memories stirred; I felt myself falling back into that familiar vortex, all alone. I swiped at my sudden tears. “I owe them an intact family life.”

“Three years from now, do you think you’ll be happy with that decision? Imagine what you’d think every time you looked at one of your children.”

Sit quietly, close eyes, picture Lynn floating away from me, feel my joy ebb away, chasing her down the stream. “I’d probably resent them.”

“How would that be for them?”

I looked out the window, blinking furiously. I didn’t want to cry here. I needed information, not sympathy; facts, not emotion.

“Ginny,” the therapist spoke more gently. “Your kids need a happy mother. Without that, their lives will be much harder. I can help you bring your children through this. It won’t be easy, but they’ll be okay.”

What? I didn’t have to choose between my children’s happiness and my own? Wait a minute! I had blamed my mother for pursuing her happiness at my expense. Now I should forgive her just because a therapist suggested she did the right thing?

Memories crowded in, challenging the judgment and fury of my fifteen-year-old self. I scanned those faded images looking for signs of my mom’s happiness. Nothing. I saw her curled up under the covers, crying alone in her bedroom between sips of cold coffee, castigating my father for having left her, stumbling through her days incoherently, losing her children, her apartment, her sense of purpose.

She didn’t pursue her happiness; she barely survived. She tried to contain her agony and numb her pain. When she lost her footing, her problems magnified and multiplied. She could hardly hold on to herself; no wonder she couldn’t attend to her children.

A way forward started to open up as I sat quietly. No one suggested I avoid my children’s pain. But don’t sell out in the name of loving them. I’d sold out before and look where I had ended up. Right here. My survival wasn’t at stake, just my happiness. If my marriage ended, I wouldn’t lose myself. The real question was what would happen if I stayed.

The sweetness of a life with Lynn beckoned. I couldn’t deny how bright it looked, how much I wanted it. Maybe the future could unfold differently in this newest iteration of family if I took the leap.

Fear. It never stops. It’s always jumping up and down to catch my attention, waving a red flag about the future. A major crisis lurks ahead. Duck and cover. I spent nearly thirty years warding off potential dangers, bracing for problems that never materialized, and protecting myself from nightmarish fantasies that may have had some basis in the past, but had no basis in the present. I had done enough push-ups by now. I had nothing more to prove to myself.

Enough already.

I wouldn’t ignore my children’s suffering. I would acknowledge their loss. I would sit with them when they wept—not sidestep or sugarcoat their pain, but hold their hands and listen. I would not leave them alone with their grief. And I would make my relationship with this marvelous woman work, not just for me, but for them too. I would do the hard work required to build a life with her, big enough to include and welcome them. They would live in a household headed by grown-ups who wanted each other, who sought and maintained connection. We would all learn the truth about love, its high-flying ups and messy downs, its bargains and trade-offs, its hugs, kisses, and bouts of yelling. We would thrive.

Despite all the uncertainty I had struggled through, the confusion I had battled, now that I could see the road ahead, I knew I would stay the course. There would be no second-guessing or turning back. Before, I had been tough enough to buck up and shut down; now I was tough enough to show my vulnerabilities and risk pain and loss. I would have the hand of the woman I loved to pull me up and calm me down, to steady me and hold me. She would show me the way if my steps faltered or my fear threatened me. I wouldn’t have to negotiate this life alone, waste energy to keep a secret that only hurt and never helped. I would get to live out loud, and love it.

Within six months of picking up that ChapStick and daubing Lynn’s lips, my marriage was over and Josh had moved out. Time played tricks on me during that period—everything happening so fast, yet slowly enough to allow way too much opportunity to weigh options and consider consequences. In retrospect, it all felt like a disconcerting dream, rushing down a corridor filled with open doors, a fierce wind chasing me and slamming each one shut before I could grab the handle and peek inside to decide whether to enter. It turns out there was only one route and one exit.

I broke my children’s hearts. I destroyed my husband’s trust in me and lost him as a friend. We hired lawyers and initiated our divorce proceedings. My friends knew our marriage was dead. Josh’s parents and family heard the horrible news. I sketched the scene for my siblings, swearing Peggy, Muff, and Richard III to silence. The story of my affair rippled through the families in my daughter’s kindergarten class; I heard the whispers and felt the stares at the school playground and in the classroom.

Three thousand miles lay between me and my parents. To them, I’d said nothing.

I looked in the mirror and imagined my father’s affection and respect evaporating when I repainted his image of me with one bold stroke. I had avoided thoroughly disappointing him my entire life. I could see his downcast eyes and hear his voice in my head, and I didn’t have to work hard to imagine his words, “I’m disappointed in you” and “I thought you would know better,” challenging my resolve.

Was I ready to take this step, to let us both know that forever going forward, the force of his will was not going to trump mine?

It was now or never.

Late morning sunshine filtered in the kitchen window as I sat at the table with a pen and a notepad of yellow-lined paper. After a minute or two, I lay down along the cushioned window seat and stretched out in the sun, arms cradling my head, eyes closed. Words and phrases drifted in and out along with random thoughts. No guts, no glory. Birds chattered and twittered in the evergreens beyond the deck. Leave it all on the water. Jet engines rumbled above. Row your own race. I listened to the rhythm of my breathing as I thought of things to come. No pain, no gain. The waters ahead did not look particularly gentle; a slight wind had kicked up and small waves ran up against the current. Not quite whitecaps, but the going would be choppy. Time to turn into the wind and dig in.

I set the pad in front of me, uncapped the pen.

Dear Dad,

I’ve thought about writing you for a while now. I know I told you that my marriage wasn’t going so well, but I didn’t tell you the whole story. I’ve fallen in love with someone else. That someone else is a she. Her name is Lynn.

I don’t know how it happened. All I can say is that she is worth all the pain of leaving my husband, hurting my children, and disappoi

nting you.

I hope you can understand. I know this will be hard for you. You are very important to me; I love you. I want you to know the truth about me, even if it makes you stop loving me. It’s been a long road, but I know I’m headed back on course.

20

Eight years later, on a gray and chilly January afternoon, I stand on the sidelines at the Starfire Soccer Complex in Tukwila, Washington, as my daughter tries out for the Olympic Development Program (ODP).

Fourteen-year-old Sierra is a forward, a player whose shots have a nose for the back of the net. The coach, inexplicably, has put her on defense. Why isn’t he letting her show her stuff? But I know my mama bear instincts have no place here. I scrunch my chin into the collar of my pile jacket, shove my hands into my pockets, and clamp my teeth together. Sisi’s doing fine. Her foot skills are sure, field vision excellent, and passing precise, no matter where she’s put.

This tryout is merely a formality. Everyone has told Sierra she’s a shoo-in for the team: her reserved and understated premier club coach, her soccer guide for the past three years; her high school coach, a rock star at hard ass; the mother of a current ODP player who has already added my name to the team’s e-mail list.

The practice rolls to its end. Now the coach is talking to Sierra on the sidelines. Good! My hands clench and unclench in their respective pockets. Sierra nods okay and strides off the field, a girl on a mission, grabs her backpack lying near the bench, comes up to me, barely pauses, keeps on going. “Let’s go, Mom.”

I start to speak, but I can’t. I fall in step with her.

Her expression impassive, she says quietly, “I didn’t make it.” I hear the break in her voice.

When the car door closes, the seat belts are clicked in, the engine started, her tears come: “I’m not good enough.” The grief and pain of a lost dream.

Focus. Breathe. My daughter’s dream has been derailed by a man who can’t see how talented she is. My anger won’t help. My tears won’t help. I can’t fall into the abyss that has just opened up within me; this is not the time.

Sierra is crying almost too hard to talk, playing back the coach’s words between her guttural heaves. “He told me that I had to be a lot better than anyone on the team to get picked. I had to be better if he was going to cut someone. I’m not better.”

She keeps going, slowed by her sobs. “I don’t care. I didn’t want to be on that team anyway.”

I keep driving; Sierra is nearly choking with heartbreak, keening like a wild animal, injured and abandoned by its pack.

My memories come flooding back: the burn of wanting something so much yet being left behind; the agony of being labeled “not good enough”; the fear of what failure would mean about me.

Rowing taught me toughness and gave me the confidence to believe in myself. My beloved sport gave me a testing ground for standing on my own two feet, for discovering I could go my own way and my world would not disintegrate. After all, my father did not stop loving me when I ignored his advice and kept rowing after three years of being cut by National Team coaches. But ultimately, not even my ascent to Olympic heights could teach me my most fundamental life lesson: I was my own person with my own life to direct. Nothing, not fear or the prospect of loss should deter me.

No one had ever taken the time to assure me that I could not lose if I followed my heart. No one had ever realized how badly I needed to hear those words out loud.

I was an ordinary girl when it all began, with a mother who was ill and a father who needed distance from both his feelings and mine. Ordinary, that’s what I was, a preteen whose understanding of the world was skewed, who mistrusted herself and her potential as a result, who had to fight the world harder because she thought she wasn’t quite strong enough or good enough or lovable enough to win as she was.

That’s what we all are in the beginning—ordinary—with the same ingredients poured into our psyches: the capacity to learn, to love, to stand up when we are shoved down hard by life, to persist in the face of agony, to listen to the quiet of our hearts when the world is shouting we are wrong, and to keep becoming ourselves. I reached the near-pinnacle of extraordinary by developing ordinary qualities, by honing my capacity for self-discipline and channeling my nearly debilitating fear into an imperative to go forward, regardless. I developed some of the muscles we are all given. I did it the hard way, alone and afraid much of the time.

I turn and look at my precious daughter, still sobbing. I will not leave her to draw her own wrong conclusions about the afternoon that has just ended. I cannot make her feel better, and that’s not the point anyway, but maybe I can help her avoid the mistakes I made so long ago.

I say quietly, “Sierra, are you going to let one coach who watched you for one practice decide how good you are?”

No answer. She keeps sobbing. “You’re going to let him have that much say about your future?”

She glances over at me. I continue, “One hour, that’s all he saw. Does he know more about you than you do? Than the coaches who have worked with you for years?”

I take her hand and hold it, driving left-handed. Sierra knows I was an athlete; she grew up playing dress-up with my assortment of medals and knows that one of them is Olympic silver, hanging from a ribbon colored with the pastels of LA’s 1984 Games. But she doesn’t know everything.

“Have I ever told you about trying out for the Olympics?” She swallows and shakes her head. Her sobbing slows to crying. A half-hour drive home lies before us, more than enough time.

By the time I finish, we are nearly home. I pull in the driveway and turn off the ignition. Sierra has stopped crying. I reach over and take her hand again, pull her over to me, and cradle her head against my shoulder. I wish my love could salve her sorrow, but I know better. Then I take her hand and say, “Sierra, look at me.”

Calm and quiet now, her usual rock-solid composure regained, she looks into my eyes.

“Don’t ever let anyone tell you who you’re going to be. Only you get to decide that. Okay?”

She nods. “Okay, Mom,” she says. “I won’t.”

We get out of the car and walk to the top of the narrow path that leads to the front door. I envelop her in a mama bear hug. A circle completes itself. I know my baby girl is going to stay on course, regardless of the inevitable winds and waves that her own row will take her through and the currents that will buffet her.

I breathe deeply. I realize how far I’ve come; the young girl inside me, now well past forty, has fully claimed her future. I’ve never had any trouble dredging up painful memories, however measured—in years, in tears, in forgotten half-empty cups of bitter, cold coffee. But I often wondered what happened to my happy moments. Where were they? Why didn’t they ever float into my thoughts?

The good of my past was there, burrowed deep inside, well beneath the expectations and the “shoulds,” smothered by the buck-ups and shut-ups. Yet not lost; rather, I now realize, waiting for an invitation and a warm welcome.

Those good memories swell within me as I stand with my daughter. Here they come, like water from a stream finally undammed, a spigot finally unblocked; a dribble at first, and then I’m drinking from a fire hose …

Mom’s piano tickle game, her goodnight kisses after a fancy night out, her perfume wafting sweetly while she gently pulled my thumb out of my mouth; Swedish meatballs with creamy gravy, mounds of thin pancakes, happy homes for butter and syrup; Christmas Eve parties rich with company, center-pieced with a groaning smorgasbord, stockings filled with silly gifts from Mrs. Claus; all those East Hampton summer days on Briar Patch Road, filled with days at the beach playing in the waves, sunbathing, building sandcastles; camping under the stars and waking up beneath dew-soaked blankets; swinging in the hammock with Dad; our underwater somersault contests; the penny doctor, invented by Dad to soothe a stubbed toe or salve a skinned knee; playing box ball, hand ball, and running bases on the city’s sidewalks; my first-ever run around the reservoir, hot sun, baref

oot, a long mile and five-eighths, inspired by Dad’s patience and cheerleading to make it all the way without stopping, even though I was dead slow.

I remember that October day when I was sixteen and miserable, standing on the banks of the Charles, seeing those string-bean-slim boats for the first time. I remember falling in love with the oars splashing, the sunlight dancing, the synchronicity, and the power and control. I remember wanting to make it all mine.

Inside me, the river runs deep and clear now.

Standing by the shores of Lake Casitas, the desert sun reflecting off the shiny silver medal newly around my neck, I raise my head and see my family in the crowd, waving and cheering wildly. I feel the tug of my teammates’ hands as we thrust our arms high above our heads. We did it. I did it.

“Let it run.” Finish your stroke, let your hands come out of the bow in the first part of the recovery; pause on your slide, lower your oar handles into your lap so that the flat blades glide high above the water. Sit still as long as you can, balancing to prevent any oars from slapping the water. The boat will slow like a magnificent crane skimming over the water, until it finally comes to rest of its own accord.

Epilogue

Diana Taurasi, the undisputed star of the Phoenix Mercury in the Women’s National Basketball Association, has just hit a trademark twenty-two-foot three-point shot on the run and is strutting down the court, tugging the upper corners of her jersey front in the classic “ain’t I grand” gesture of athlete show-offs, smiling gleefully as the crowd roars its adulation and approval. I want to strangle her for gloating before the end of a game, rubbing in the drubbing.

Course Correction

Course Correction