- Home

- Ginny Gilder

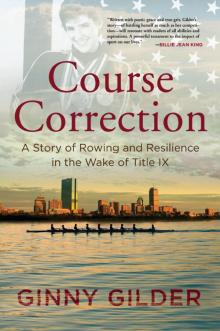

Course Correction Page 24

Course Correction Read online

Page 24

By New Year’s, I felt the first faint flutter of my baby’s movements, as gentle as a butterfly’s kiss; I kept training. I biked down to the University of Washington shell house to lift weights throughout the winter months, huffing and puffing up and over the hill that separated the university district from our house in Fremont, in rain or less rain. I jogged increasingly slowly, stopped running stairs and hills, and reverted to walking them, as my doctor instructed me not to run my heart rate up into anaerobic territory. No excuses, no missed workouts for me.

I kept track of my appearance with regular mirror checks; my upper arms retained their muscular curves with no incipient sign of sagging, my quads still bulged, and now, so did my stomach, my own private hill, challenging me to respect its power. And that baby was powerful; I was growing more tired and seemingly less fit, no matter what regimen I maintained. Halfway through, nine months of sharing my body already seemed too long, and I was ready for freedom, freedom to drive myself hard again and focus on my own needs and wants. Resentment pricked me whenever I confronted the fact that I had to downscale my training to accommodate my baby.

By Mother’s Day, Josh and I were settled into our new home in the northwest, and the baby’s room was ready. We whittled down our list of names to one boy’s and a handful of girl’s. I was positive I was having a girl. If only she would get here already; pregnancy was clearly not for me.

The last weeks brought me to the brink of my self-control. I started walking stairs in my neighborhood to urge my baby into labor sooner, despite my doctor’s concern about my increased blood pressure and caution to minimize my activity. I ignored her instructions to spend as much time as possible lying down. I ranted internally, unhappy with having allowed an alien being to occupy and reshape my body to suit its own needs. Here I was, a trained athlete at the peak of her competitive career, enduring the bodily occupation of pregnancy: the weight gain, loss of muscle tone, the attendant decrease in mobility, increased exhaustion, and the necessity to modify training and put another’s needs before my compulsions.

I was less than wholly successful in accepting those restrictions. I was the same girl who overtrained for the Olympic trials, who ignored her coach’s guidance and her physical therapist’s instructions; now I could not comply with my doctor’s orders. I couldn’t imagine the worst that could happen. Until it did.

“Way enough. Hold water!” When a coxswain calls out that pair of commands, a crew responds instantly. All rowing stops and every squared oar digs deeply into the water, killing all forward momentum.

The commands are a survival call, designed to halt a shell moving at maximum speed. A sudden crisis looms ahead: the coxswain has detected some object in the boat’s path, perhaps some flotsam in the water, or a sculler in a blind boat rowing against the established traffic pattern, or a pleasure boat gone overboard on fun. The coxswain has to avert disaster. Maybe she’ll be successful; maybe it’s too late. Perhaps she should have noticed the obstacle sooner, but was distracted by the goings-on inside the boat or absorbed by her own anxieties. Maybe the sunshine of the moment blinded her to whatever lay straight ahead. Perhaps she did notice, but misjudged its proximity and discounted the risk. Perhaps she assumed the problem would disappear before her crew reached its spot on the water.

Regardless, at the last moment, she recognizes there’s a problem. She alerts her crew. And the shell stops, dead in the water.

The day started with so much hope. I woke to the gentle contractions of early labor. I dialed my doctor’s office.

“Dr. Lardy, I think contractions have started. I already had an appointment scheduled for this morning. Do you want me to come in?”

“It’s up to you. You can skip it and just come to the birthing center later, when the contractions get stronger.”

“I think I want to come in. She was pretty quiet last night at the movies.” During Three Men and a Baby at the Seattle Film Festival, what I hoped would be my last big night out before becoming a full-fledged mom, I had shifted my tummy to see if I could wake her up. I was rewarded with a poke in the ribs as something bony—her elbow—nudged me, and I sat back, reassured. Yet this morning, that faint concern had fluttered back up to the surface.

“No problem. I’ll see you in a little while.”

Sitting in a drab examining room, on the corner of Madison and Broadway, Josh and I waited for Dr. Lardy. She bustled in and smiled. “Okay, looks like today’s the big day. How are the contractions going?”

“They haven’t really changed. About five minutes apart. Not too bad yet. I can take it.” I grinned.

“Well, let me just take a listen and make sure all is well.”

I pulled up the hospital gown covering my stomach, now stretched taut, and Dr. Lardy donned her stethoscope, bent over, and placed the chest piece below my protruding belly button. She listened intently for several seconds, moving the cold stainless steel circle around my vast belly. Standing up, she frowned slightly.

“I’m going to use the ultrasound to locate the heartbeat. For some reason I’m not picking it up with this. That happens sometimes.” She pulled the stand that held the machine over to the examining table, squirted clear connective gel on my abdomen, and smeared it around.

The quiet room grew more still, as she sat down and moved the wand across the gel. She bent over me more closely and focused all her attention on listening. My heartbeat ratcheted up as she kept shifting the wand’s position and my tiny flutter of concern ballooned into anxiety. I looked at Josh and shivered slightly. He was watching the doctor’s movements and didn’t catch my glance.

Dr. Lardy sat up straight and turned away to switch off the machine. When she turned back to me, her look of concern propelled my anxiety skyward. “I’m going to send you over to the hospital to get an ultrasound on one of the larger machines.”

I asked “Why?” knowing the answer.

“They’re more sensitive and should have no trouble picking up the sound. There must be something wrong with this machine. It shouldn’t be hard to find the heartbeat of a full-term baby.” Nonetheless, Dr. Lardy looked grim as she told me to get dressed and left the room to call the radiology department.

The floor had disappeared. How could I stop the sensation of falling? Who had shoved me over the edge?

We crossed the street and walked over to Swedish Hospital for our emergency appointment. We sat in the radiologist’s waiting room among a group of placid patients, betraying no emotion or strain. I sensed the hand of doom hovering, ready to snatch away our happiness. I was helpless to stop it, as if a nightmare had replaced my real life, relegating me to observer status.

In the examining room, I watched the radiologist move the ultrasound wand over my protruding belly, searching for my baby’s heartbeat. I saw his concern deflate into defeat. He would not meet our eyes as he put away the scanner and wiped the gel off my stomach.

I knew he wasn’t qualified to read the test result, but I couldn’t stop myself. “She’s dead, isn’t she?”

His head barely nodded up and down. “Yes, I’m very sorry,” he mumbled.

He left quickly. I couldn’t blame him—no one would want to be the bearer of bad tidings to an expectant couple, to kick them in the stomach, knock the hope out of them—but I did.

Fury gripped me. “He wasn’t going to tell us? Make us go back to the doctor’s office to hear the official news? What kind of crap is that?”

Josh took my hand and looked into my eyes. I saw bleak despair in his face, his features sagging. He started to cry.

I stopped talking. All the anger in the world was no match for the truth. She was gone.

Not fair, not fair. Such an inane protest, as if a judge or jury could magically appear and reverse reality. How could this be happening? Disconnected and dazed, I didn’t cry.

The everyday sounds of our surroundings dropped away. We walked to the elevator and waited, clutching each other by the hand. We stumbled back to the doctor’s office

, across the street from the hospital, no longer a hop, skip, and a jump.

What happens when an expectant mother has a dead baby inside her?

Dr. Lardy was gone. Her office didn’t know where she was. I had lost my baby and my doctor. The receptionist paged her and pointed me to a phone a minute later.

“I’ve been looking all over for you,” my ob-gyn said frantically.

“We came back to your office,” I stammered. “No one gave us instructions. We’ve been waiting for you here.”

“Get over to the hospital right away. We have to deliver the baby.”

But it no longer mattered whether we hurried or not. I knew what waited at the end of my labor, and I could barely move, as if the numbness I felt had leaked into all my muscles.

Way enough. Way too much for me. I didn’t stop in time. I crashed into my future and crumpled on impact. I didn’t see it coming. For once in my life, I hadn’t been braced for disaster. I had not prepared for this.

Hold water. Mine broke, filthy brown with the evidence of my baby’s distressed last minutes, her fecal matter expelled in her death throes.

When Josh and I finally reconnected with Dr. Lardy at the hospital, she settled me into a labor room. “I want a C-section,” I told her.

“Absolutely not. There’s no medical justification for that.” She sounded so businesslike, chilly and distant. I hated her. I couldn’t think of any better rationale for surgery than to avoid the horror of enduring a labor without any payoff. Her horizon was broader than mine: she was thinking about the added difficulty of recovery from a major medical procedure. But I simply hoped to survive giving birth to a dead baby.

“I’m going to give you some Pitocin to stimulate your contractions. Your labor will need some help to get started now that …” She paused, took a deep breath, and kept up her poker face, “… your baby can’t help. I can give you some painkillers if you like.”

If ever there was a moment to buck up and shut up, this was it.

“No thanks,” I said. “She might be dead, but I can use this delivery to practice for the real thing. Train for the next one.” Maybe a brave face would get me through this nightmare.

Dr. Lardy respected my decision and set up an IV drip for the Pitocin. As I lay on the gurney, my tears finally came.

The contractions strengthened. The facts raced around and around, unchanging. My sobbing increased in intensity and volume. Even the concentration demanded by childbirth could not overwhelm my outpouring, which must have echoed beyond my hospital room and disturbed everyone else on the labor and delivery floor.

The doctor gently insisted on administering a tranquilizer.

My daughter died the day after her due date. I gave birth to her the next afternoon. She was named Liala Ljunggren after two of her great-grandmothers. I never saw her breathe, never heard her cry, never saw her open her eyes or unclench her fist. Her seven-pound, eleven-ounce body had all its fingers and toes, perfect ears, a head of dark hair, her red lips shaped like her father’s. Strips of her skin had begun to peel away after twenty-four hours of floating dead in amniotic fluid.

We called our parents from the delivery room. I didn’t reach my mother, but my father was still at the office. He was short and stiff, his voice gruff, all business. “Well, Ginny, you win some, lose some. Sounds like you lost this one.”

We spent the evening and the next morning holding our daughter, bathing and dressing her. She smelled sweet, not dead. Her fingernails needed trimming. Lost promise flaunted its victory, while we cuddled her, took pictures. We said our goodbyes, even though we never had the chance to say hello.

I had brought this disaster on myself, on my baby girl. The terrible truth gnawed me from the inside. I killed her, my Liala, with the ruby red lips waiting to be kissed, the chubby upper arms good enough to nibble, the tiny fingers with their too-long nails.

Dead and gone, thanks to me. Because I did not listen to my doctor when she insisted on bed rest during the last two weeks of my pregnancy. It didn’t matter that she explained the risks of toxemia. It didn’t matter that she showed me the graph of my blood pressure rising. Because who lies in bed during the middle of the day? I knew the answer to that question: Weak women. Crazy women. My mother. It was drummed into my psyche so deeply that I couldn’t see it any other way. Of course I had to get up, soldier on, and fend off my mother’s fate.

This voice of fear had governed my decisions for years. I believed it protected me from disaster.

I had listened to that voice the day after my daughter’s due date when I went shopping at Keller Supply in Ballard, musing about plumbing fixtures and comparing prices instead of lying in bed. A rush of abdominal pain doubled me over and sent me scurrying into the ladies room to expel the gas I thought was cramping my insides. I sat on the toilet, needlessly I discovered, without relief. After a few minutes, my internal chaos subsided and all was quiet.

No alarm bells set off inside me, as I blithely ignored my doctor’s orders, but my daughter died then. I mistook her death throes for an upset stomach, but I noticed her eerie quiet that evening. No soft bumping against me. No nudge under my ribs. The first feather of concern brushed across my thoughts, but its touch was gentle enough to ignore.

I woke up early the next morning to faint signs of labor, and still I insisted on going for a long walk. Again I ignored my doctor’s orders; again I accepted the dominance of that fear-fed internal voice, yielding to the imperative for action at all costs. I wandered down the long, gently sloping hill from 42nd and Whitman Avenue North and stood in the middle of the Aurora Bridge, looking east at the Cascade Mountains. Leaning over the railing, I wondered if my daughter was finally ready for me, and I for her.

I didn’t realize that my fear had hijacked sound judgment and taken her life in the bargain. It took an unimaginable tragedy to jolt me awake: I was listening to the wrong voice.

A week after her stillbirth, I received the call from the funeral home that Liala’s cremation was complete: I could pick up her ashes. Then I went to the doctor: she should have been weighing my newborn and cooing over her good looks, but she only had my recovery to monitor. My blood pressure had returned to normal; my breasts were swollen with useless milk. My body was behaving on schedule in a world thrown off kilter.

And I could no longer keep the truth to myself. I began to sob, “It’s all my fault.”

“No, it is not your fault,” Dr. Lardy said, her stern expression turning even more serious.

“It is.” I regaled her with my litany of evidence; how many times I defied her advice, what a spectacular failure I was when it came to bed rest.

She defended me. “Normal stillbirth means they don’t know what happened. The autopsy didn’t reveal a specific cause of fetal death.”

I shook my head and continued to sob.

“It’s most likely that her cord got kinked. You had nothing to do with her death. Ginny, I mean it.”

I knew better. I nodded: “Yes, I hear you.” I certainly did not mean “Yes, thank you, I believe you.”

Nothing I had lived through prepared me for this grief. I lay in bed every morning under the quilt my mother had sewn for me, wondering if I had any reason to drag myself up. Was this what my mother had experienced when her life changed overnight, when her marriage died without any apparent warning? The profound sense of dislocation from the life she regarded as normal, of being in freefall from what she knew, clueless about where she would land, or how; the surreal experience of walking through a world where everything looked ordinary, business as usual, while internally she felt ravaged, empty, and useless, with nothing to live for?

Every time the phone rang, a wild hope surged through me. It was the hospital! They had made a terrible mistake. They’d found my baby. She was fine. Please come get her, right away.

They told me healing would take time: two years was normal. There was nothing normal about losing my baby.

Life ground to a halt. I doubted my su

rvival. I saw myself sliding toward my mother’s escape hatch, the lure of a soft bed with pillows to burrow into, covers to crawl under. Impenetrable darkness surrounded me, as if I’d entered a bleak forest, the trees so thickly entwined that no sunlight could break through. I couldn’t see a path forward, and I didn’t care.

Lose your parents, lose your past. Lose your child, lose your future. I wandered through my days, crying constantly. I passed a church and realized I would never see my baby get married. A child running down the street reminded me that Liala would never graduate from preschool, much less college. Overhearing a daughter arguing with her mother, I understood I would miss every argument with my girl, who would never scowl and stomp out of a room muttering, “You’ve ruined my life.” I would miss watching her grow, learn to read, kick a ball, do a cartwheel, pick up an oar. I would never hear her dreams whispered into my ear as we snuggled together. I would never, ever get to cheer her on from the sidelines and stand by her, win or lose. Everything. I would miss everything.

As for rowing, what was that? Who cared? The Olympics? Training? Tell me why propelling a flimsy manmade hull faster than anyone else mattered. Not to me. Not anymore.

Ten years of caring, gone. A decade of wanting, vanished. All those lessons learned of toughness and self-confidence were no match for my grief. A carefully constructed life, focused and purposed, was dead in the water.

PART IV

Recovery

17

The trait most commonly associated with rowing is that of extreme exertion, yet that’s only half the story. Muscled might cannot alone create the beauty of a well-rowed shell. The drive and the recovery together make up a complete stroke, linked to each other by the catch and the release, the markers that signal the transition from one state to the other.

The recovery follows the blade’s release from the water, a span of effortlessness when the boat flows forward on its own momentum. The quality of the recovery determines the fluidity of that forward motion. Imprecise synchronicity or rushing the return to effort can ruin the promise of these breaks in effort.

Course Correction

Course Correction