- Home

- Ginny Gilder

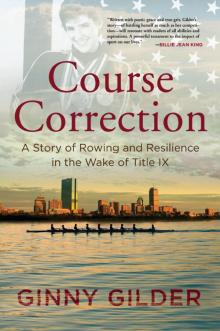

Course Correction Page 22

Course Correction Read online

Page 22

Still, he stayed in my corner. He made me talk to him about what had happened, and he made me listen to his reaction, both his fury and grief. He forced me to reflect on what I had done: my reluctance to seek support when I was floundering, my insistence on going my way alone, and the resulting disaster and disappointment. How my fear directed me. How it was in charge, not me.

A lot of people would have given up on me. But Harry didn’t disappear; he rallied: “You can win these trials if you decide to. It’s up to you.” He took me out on the water, watched me row, and corrected my technique. He listened to my outpourings of despair and reminded me that I could decide how this story was going to turn out. I didn’t tell him that I could see no happy ending: every stroke was painful, even on the paddle.

We kept working. On my last day in Boston before flying out to the trials, I took my final row. I told myself how much better my side felt. No soreness. I fantasized that my healing had started. By the time I landed in Long Beach the next day, maybe I’d be able to take some hard strokes.

Long Beach was a disaster. It couldn’t have been otherwise. I went in the favorite and exited an abject failure. I looked good on the outside, but was a total mess on the inside. Harry and Lisa were three thousand miles away. No one in Long Beach rooted for me; I expected nothing more. No one knew I was injured until the trials were over. I would give no one the chance to gain a psychological edge, nor would I allow myself a smidgeon of a justification for poor performance.

The entire Olympic sculling team would be chosen from the two dozen entries. The winner would represent the United States in the single. The coach of the quad would choose the next four through a selection camp process. The remaining athletes would pair up to race in another set of trials for the double. But I only had eyes for racing solo and claiming gold. Settling for a seat in a team boat smacked of failure. So I refused to contemplate plan B, as I couldn’t think about losing the singles trials without panicking.

Racing was miserable. I got slaughtered in my first heat, losing to Lisa Rhode by more than three seconds—an eternity in rowing. I’d known I was in trouble before the race, but now everyone else knew, too. To earn a spot in the finals, I would have to win a repechage heat—a second-chance race for all the entrants who had lost the first round—and finish in the top three in the semifinals. I would go to the line three more times, if I were lucky.

After my first race, I half wished the ground would split open and swallow me, free me from the torture that lay ahead. I couldn’t bear to contemplate losing the single and not making the Olympic team. Life as I had dreamed would vanish. The fast-approaching public humiliation already smarted, and my desperation ate me like acid.

I called my father from a phone booth at a noisy intersection, sobbing, “Dad, I blew it. I lost my heat.”

“Ginny, I can’t understand you. What did you say? Slow down.”

I spoke more clearly. His response? “The question is, how much do you want it? How tough are you?” He was concerned, but he didn’t realize what I was worried about. If he had known I was afraid of losing so much more than the race, maybe he would have known how to reassure me. But we had no history of talking about the hidden doubts that drove me.

“I do want it,” I said. “But I don’t know if I’m tough enough.”

We hung up. My dream was teetering. I had set myself up for impossibility and even I was not a superwoman.

Although Dad couldn’t provide any verbal reassurance, he flew out for the semifinals and finals over the weekend. He watched me struggle without comment or judgment. He didn’t run away, but offered support.

The next race, my repechage, was better. I eked out a victory against weak competition. The semifinals were next; the top three would progress to the final.

As I contemplated the semifinals and the increasing possibility that I might not win, I finally started thinking about the selection process for the quad. Even if I couldn’t win the trials, I had to perform well. Even if I couldn’t be the single, I wanted to make the Olympic team. I needed to position myself for the selection camp. I had to make the finals.

Harry coached me over the phone: “You have to maintain contact during the first four hundred meters. Don’t lose your head or your control.” Racing had taught me well to ignore pain, but this time it was so jarring and so deep that I expended huge resources of energy to override its compulsion to stop. I had to force myself to pull the first few strokes off the line of every race, knowing that every catch would stab me. Ten strokes in, the normal pain of racing took over and I forgot my injury in my competitive frenzy. Every time I crossed the finish line and stopped rowing, the intensity of the reemerging pain made me dizzy. Still, Harry intuited correctly that if I could survive the start, I could live through the aftermath.

But my start in the semifinals was horrendous. I was solidly in fifth place, unsuccessfully challenging Joan Lind for fourth, admonishing myself, “Don’t stop!” The pain made it hard to steer; I veered off center toward the starboard buoys of my lane. As I dropped my oars into the water for the next catch, my starboard oar tangled in the buoy line and caught under the water. My port blade reared up like a flagpole and propelled me over my submerging starboard rigger.

I landed in the water beneath my upside-down boat. This race was over. That was it. My feet released from their foot-stretchers, and I swam to the surface and grabbed my hull to stay afloat. The referee’s boat pulled up seconds later and I climbed aboard, dripping wet, embarrassed, and disappointed. I had lost my chance to make the finals.

Still breathing hard and a bit stunned, I reached over to right my single so the launch could tow it back to the dock. The head referee, Pat Ferguson, announced, “You were in contention. We’re going to rerun this race.”

What? The race was nearly half over! Contention? What contention? What was she talking about?

Surely she wasn’t talking about me. I had passed the four-hundred-meter mark before I flipped, far beyond the one-hundred-meter breakage allowance. I wasn’t anywhere near the competitors who’d been vying for the top-three finishing positions.

But I had forgotten that Pat witnessed my come-from-behind finals qualification at the Worlds eight months earlier from the bird’seye view of the referee’s launch. She saw me come out of nowhere and plow through the field to nab third place and a position in the finals, and row to a bronze medal the following day. She wasn’t going to let the favorite sink so quickly out of contention, not after what she’d seen at the Worlds.

Having stopped the race and informed the other competitors of her decision, Pat directed the launch driver to head for shore. As we puttered by another rower in one of the adjacent lanes, I glanced at her. One of the Long Beach sculling crowd, another tall, well-proportioned Olympic aspirant, Beth Holacek, glared back at me.

“Hey, Beth, I didn’t do this on purpose.”

“Sure looks like you did.”

I marveled at her conclusion. She unduly credited me with enough guts and quick thinking under pressure to flip myself and rely on a referee to stretch the meaning of “in contention.” Maybe it was easier for Beth to think I’d bailed on purpose than to believe I had simply rowed badly.

At the dock, the referees explained their logic. The Olympic trials were designed to select the fastest boat possible. Eliminating someone because of onetime bad steering could hurt US prospects at the Olympic Games. Of course, steering is part of racing, and poor steering slows boats down: I was pretty sure if a different somebody had flipped at the same point in the race and in the same relative position to her competitors, the race wouldn’t have been recalled.

But we re-rowed. And Pat Ferguson was right. At the halfway mark of that race, I was in sixth place. Then the pain receded, and once again, I managed to pull off a mighty sprint, sneak into third place, and earn a spot in the singles finals.

My luck and determination took me far. But winning the trials required perfect preparation, and mine was anythin

g but.

So the following morning, my dream of singles gold officially died in the finals of the Olympic trials. I lacked power and intensity. I ended in fifth place.

In the time it took to row from the finish line to the dock, I had to decide whether I could put aside my crushed dream of stardom in the women’s single and accept an alternate vision: reform myself into a team rower and compete for a position in the quad. If so, I had ten minutes to transform from a prima donna into an affable, easy-enough-going contributor who wouldn’t insist on being the center of the universe, who could respond to direction from an unfamiliar coach and a take-charge coxswain, act like racing in the quad was her hands-down first choice, give up her solo dreams, and smile through her grit-toothed disappointment.

I hated losing. But I hadn’t lost it all yet: the single was gone, but the Olympics remained within reach.

My earliest training in buck up and shut up served me well once again. When I landed at the dock, I was all smiles. I congratulated Carlie Geer, the winner. I mingled with the rest of the finalists, comparing notes about our racing. At Harry’s insistence, I finally disclosed to John Van Blom the injury that had derailed my racing. At least the pressure was off. I had landed with a bump back in the familiar land of underdog. I knew the rules of engagement in this territory.

But I still didn’t know what the damage was, because I’d refused a diagnosis before the trials. Now, however, I needed to know the score. Selection camp started in less than forty-eight hours. The Olympic Games were less than three months away. John would not choose an athlete whose injury had no chance of healing well in time.

The day after the trials, I visited a sports medicine doctor in Los Angeles. He took X-rays and, showing me the little white line, said, “You have a broken rib under your right arm.”

“What? How long will it take to heal?”

“Oh, probably a couple of months.”

“Can I row on it anyway?”

“Broken bones need inactivity to heal.”

“No way. The selection camp starts tomorrow!”

“Well, you’re not the only elite athlete who’s injured. Many of our best athletes won’t be competing in Los Angeles this summer.”

The hell with that. I am going to LA. Forgetting my manners, I stomped out of his office and called Harry. After consultations with his local medical team, he called me back with their prognosis: the rib would heal with rest. I needed some time, but I would be ready by August. I just had to convince John Van Blom.

Harry helped there too. He talked with John. Given what I had put him through, I couldn’t believe Harry would sing my praises, but he made a sufficiently convincing case for putting me in the boat. I was one of two American women currently competing who had won a medal as a sculler. I’d proven myself, despite my showing at the trials.

I must have done something right during the camp to bolster Harry’s argument, because I made the team. By a squeak. John took the women who had come in second, third, fourth, and fifth in the trials: Lisa Rhode, Anne Marden, Joan Lind, and me.

For the next month, I rowed in the bow seat, rehabbed my broken rib, and made the necessary mental adjustment to team-boat dynamics. We traveled to Lucerne to race in the pre-Olympic regatta with Marden stroking. When we returned in late June, John switched us and put me in the stroke seat. My physical rehabilitation was complete. But my short-lived confidence had abandoned me.

“What if” governed me. What if I got injured? What if my asthma kicked up again? What if I wasn’t strong enough, fit enough, tough enough? What if I didn’t want it enough? No matter how hard I trained, how many personal bests I recorded on my weight charts, my timed runs, my stadium reps, my ergometer tests, I felt the hot breath of my fear on my neck and heard its disbelieving voice rumble at me. Enough was never enough.

15

On July 28, standing in the tunnel at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, about to step onstage and join the opening ceremonies of the XXIII Olympiad, I heard the roar of ninety-one thousand voices. So much had happened since I started dreaming of joining the ranks of Olympic competitors in 1976, and it wasn’t all about me. A mere twelve years since the passage of Title IX in the United States, female participation in athletic events was gathering steam worldwide. Women’s rowing had become an Olympic sport in 1976, but now, fifty-six years after doctors had asserted that women who ran the eight-hundred-meter event in track would “become old too soon,” the International Olympic Committee had added the women’s marathon and the women’s individual road race (cycling) to the LA event roster.

The times were changing even faster now. In 1900, a total of 22 women worldwide competed for the first time in the Olympics. In 1928, the year before my mother was born, 290 female athletes competed in Amsterdam. In 1956, two years before she gave birth to me, 376 women participated in Melbourne, an increase of less than 30 percent since my mother’s birth. Now, another 28 years later, over 1,500 women would be competing under their nation’s colors in LA, a growth of over 400 percent. Women would comprise 23 percent of the athletes in LA, despite the absence of nearly the entire Soviet Bloc, as compared to less than 15 percent twelve years earlier, and about 2 percent in 1900.

More than 6,800 athletes from 140 countries (an Olympic record), including 1,566 women (of course, another Olympic record), ready to compete in 23 sports comprised the main attraction of these opening ceremonies. The vast majority had preceded the American contingent of 500-plus and now filled the track. As the host country, the US team would enter the stadium last, which meant that our athletes waited three-and-a-half hours for the privilege and missed most of the occasion. At our nearby offsite location, we overheard strains of the theme from Chariots of Fire that opened the ceremony. We were missing the biggest audience participation event ever attempted in Olympic history, when all attendees turned over the placards placed on their seats and held them over their heads at the same moment to produce a tableau weaving together the national flags of every country attending the Games.

But I didn’t mind. I was here. After four years, three more hours was no problem.

The energy was palpable; we were about to march into a love fest, and I couldn’t wait. Wearing our Levi Strauss opening ceremonies uniforms—trim, close-fitting, red, white, and blue athletic jackets with matching blue pants edged with white piping—US team members buzzed with excitement, practically pawing at the ground to get going. Sporting baseball caps, wearing funny sunglasses, and waving tiny American flags, we entered the stadium cheering wildly, laughing, and absorbing the audience’s adulation. No one thought of the fourteen Eastern Bloc countries that had absented themselves in a copycat boycott, or of Iran and Libya, which didn’t attend for their own political reasons. It was a moment for happiness and celebration, to luxuriate in connection and joy engendered by a communal gathering focused on a pure purpose. It was time to revel in the excitement for all that awaited observers in the coming days: the inspiration and awe of witnessing otherwise ordinary people attempt extraordinary physical feats that would stretch them to their limits with grace, grit, and humility.

As I walked beside Kathy Keeler and Hope Barnes, well in the middle of the American pack behind the United States banner, I cried and laughed. All the hard work fell away: the memories of sitting alone in my single at dawn on late fall mornings, kneading warmth back into icy hands so I could grasp my oars properly; waking up in the dark to run stadiums on frozen winter mornings; skipping showers after evening workouts to squeeze in extra sleep; devouring muffins and yogurt on the run as I rushed to work; the disappointment of falling short, losing races, getting cut, being injured; the joy of my successes. All those pieces to my puzzle had come together and landed me here. Any residual bitterness from the 1980 boycott evaporated as I felt the love and excitement that permeated the Coliseum. We were here. I had finally made it to the Olympic Games as a participant.

I watched Rafer Johnson, dressed in pristine white track shorts and a matching r

acing singlet, take the torch that over thirty-five hundred runners had transported across the United States from the Moscow Olympics. He carried it up a steep staircase into the upper reaches of the Coliseum. It took a moment for the flame to travel from the torch to the giant urn. Then it lit. The Olympic Games were officially open. My wait was over.

The following two weeks flashed by in an instant, packed with peak life experiences that clambered over each other like a pack of puppies. The status and glory conferred on Olympians gave me a brief stardom: athlete credentials identifying me as autograph bait and granting me entry to every Olympic venue; housing in the Santa Barbara Olympic Village during the rowing competition, with access to a revolutionary messaging service that any world citizen could use to send best wishes to any Olympic athlete; surrounded by an international cast of characters and feted with an impressive range of domestic and foreign food choices; daily jaunts to the beach across the street from the Olympic complex for a quick dip in the gentle surf of the Pacific; the beauty of Lake Casitas, the Olympic rowing venue, deep blue water surrounded by the stark brown desert hills of Ojai, far from the California coast; and, of course, finally the opportunity to race in the premier event of my beloved sport.

The field for the women’s quadruple sculls with coxswain event was narrow, with only seven teams: Canada, Denmark, France, Italy, Romania, West Germany, and the United States. The heats consisted of two races, one with three crews and the other with four. The winner of each heat progressed directly to the final. The remaining five boats would race in one repechage, with the top-four crews proceeding to the final. Ideally, we would win our heat on Monday and earn our slot in the finals without having to race on Wednesday, when the five losing crews would compete for the four remaining final spots. At the same time, I couldn’t help but ponder the pros and cons of racing three times instead of twice. If we didn’t win our heat and had to race in the reps, we would gain experience for the final and adjust both to the course and to the pressure that came with competing at the highest level. The trade-off for valuable experience, however, could prove costly. An extra race meant risking the chance of something bizarre occurring at the wrong time and knocking us out of the final. It meant expending additional precious energy to reach the final. No way would John Van Blom consider a strategy that sent our crew through the repechage to win a medal.

Course Correction

Course Correction