- Home

- Ginny Gilder

Course Correction Page 17

Course Correction Read online

Page 17

But before I left Amsterdam, I sought out Kris K. He’d made me earn my place on the Olympic team, challenging me to fight. And he’d been fair. He had judged my output, not my size. He’d recognized potential in me that no one else had ever sniffed.

“Hey Kris, I’m leaving now. Just wanted to say bye and thanks for everything.”

He was squatting next to a boat, unscrewing the riggers. He looked up at me, squinting slightly, as if trying to figure out who I was. Then he stood and grasped my hand. “Ginny, Ginny, where are you going? What are you doing?”

“I’m going home. It’s time to move on.”

“What? Are you giving up rowing? You are so young. You have so much potential.” Kris swept open his arms.

Me? Little Miss Too Small To Make An Olympic Team? I have potential? Really?

I gave him a big hug, thanking him for the unexpected gift—the news that, finally, now that I was retiring, I had potential. I looked in his tanned, deeply lined face and smiled. He smiled back.

I packed up my gear and bid adieu to my beloved sport.

By late summer, no one cared about my Olympian status. The country wanted to forget the reluctant soldiers wounded by the boycott. In my own family, patience with my decisions had worn out.

I followed my Yale boyfriend’s footsteps to Boston. In the process, I dislodged my dog, Max, from his old haunts and his long stay with my friend, David, who had cared for him all summer, depositing him unceremoniously in a new life, without his old routines and familiar friends. I didn’t know what else to do. Or perhaps I was compelled to return to the city on the Charles River, by whose banks the course of my life had changed six years earlier.

I needed a job, almost any job, but it had to be an office job, something with substance, not menial. I had already traveled far off course from my father’s wishes, and it was time to return to the life I was meant for, the life he meant for me. A million questions hounded me: What was I good at? What did I like? What could I do? How could I be useful? What did I want? I lacked answers to all of them. I simply had no idea. I knew nothing at all, except how to remain on task until I achieved my goal.

Two months into my job search, my boyfriend convinced me to give up Max, who had grown increasingly unhappy being cooped up all day in the small house we rented and was becoming progressively more vicious. He snapped at children during walks and knocked down an elderly woman, luckily not hurting her. My boyfriend located the shelter that promised to find Max a home, put the dog in the car, drove us the distance to its door, and waited in the car while I went in with my faithful companion, who did not deserve the abandonment I was about to inflict on him.

The person in charge of intake took one look and guaranteed that Max would be claimed: “He is gorgeous, strong, and sleek. He will land in a good place.” I said my good-byes, hugged him hard, and looked deeply into his eyes. I couldn’t verbalize how guilty I felt for leaving him, despite his protecting and loving me for the two years he was mine, and how much I hated that my life had changed in a way that made him so miserable.

I cried the whole way home. I couldn’t even take care of a dog.

Slowly I recovered from losing Max. The shelter called and told me it had found a home for him on a farm, where he was free to roam. The news made me feel marginally better.

Job hunting was miles from Olympic glamour. For six months, miserable perseverance and blind determination kept me company. Unable to stop myself, I made my way to the Boston rowing community, as if the waters of the Charles could reassure me I belonged somewhere. I dredged up my sculling skills so I could row on my own schedule and keep myself available for that one perfect employment opportunity lurking just ahead. The daily routine of showing up at the boathouse, getting into a boat, and working hard kept me grounded as I tried to forge my way in a brand-new world.

The Charles replaced the Housatonic. Radcliffe College’s mammoth Weld Boathouse superseded Yale’s remodeled Robert Cooke corollary. Early morning practices took over from the 3:45 p.m. bus to Derby. I left the anonymity of sweep rowing, with its focus on team, and joined the ranks of two-fisted rowers. I became a single sculler. I was a grown-up now, twenty-two whole years old, doing the right thing. Take care of myself, put aside childish toys, earn a living, and stand on my own two feet. Easy. Make a plan and do it.

Plan to leave the sparkling river behind; the smooth, varnished hulls with their fragile bottoms; the intensity of the “all for one and one for all” mission to excel; the unity inspired by shared purpose; and the eternal opportunity to defy my flawed humanity in pursuit of that perfect stroke. Ignore the ache of my empty hands, whose useless calluses stubbornly refused to disappear. Blink away the hole in my day, the loss of focus.

I ended up in an office with a boss who seemed to think that my Ivy League degree and athletic accomplishments suggested some ability to work with her customers, listen to their complaints about her software product, identify their underlying problems, and help concoct solutions. I worked standard full-time hours, eight hour days, five days per week, with limited vacation and no summer break.

I thought I could do it: leave my love behind in the name of growing up. My future was calling, that was what I told myself, but something else was browbeating me into compliance: that familiar pressure to please, the fear of losing big if I went my own way. I wanted to be a grown-up, show my freedom to set my own course, but I remained ensnared in my father’s expectations. I didn’t want to be on the receiving end of any more conversations filled with his pained sighs and pointed remarks, or to discover how life would feel without any parental support.

Intentions head one way, led by the intellect. Life goes another, yanked by the heart. Once I adjusted to the scheduling requirements of my new professional life, I found myself not giving up rowing, as I had promised, but training again. The heart wants what the heart wants.

Don’t ask me how I grew so quickly restless with the idea of settling for recreational rowing for the rest of my life, how I yielded again to the nagging drive to set my sights too high. Don’t ask me how during my first postretirement spring racing season, I found myself backing into a starting platform again, this time in a flimsy one-person shell. It was the river, calling gently. I belonged there. Rowing made sense. It made the day matter; it made me matter, if only to myself.

My non-rowing coworkers came to their jobs every day without having savored the sweetness of the sunrise, the softness of the rain pattering on the water, the roughness of the winter wind blowing icicles through the air; without having luxuriated in the hours when time stretched out like the sea’s infinite reach to the horizon; without reviewing the daily lesson that no matter what havoc humanity wreaks, life will sweep on through.

As for me, the river and my dreams swept out my best intentions to be a good girl. The river returned me to myself.

I finagled a week of vacation from my boss in advance of having earned it. Perhaps my request for time off to attend the Olympic Development Camp sounded sufficiently official and important to convince her to defy company rules and spring me from my full-time jail barely six months into my life sentence. Or maybe she got bored with my whining.

Either way, in early July I flew to Los Angeles and caught a ride to Newport Beach, missing only the first day of a sculling camp dedicated to learning, not competing. How I got an invitation to join this select group, taught by the masterful Tom McKibbon (who’d coached the first American woman to an international medal in the single sculls, the legendary Joan Lind of 1976 Olympic fame) was beyond me, but I wasn’t going to ask questions.

I joined several other scullers from around the United States to spend a week learning the finer points of rowing with two oars, equally applicable to singles, doubles, and quads. The camp had nothing to do with selection, as no team was intended to emerge from the process. There were no seat races, ergometer tests, or cuts. There was no humiliation, just encouragement.

Sculling technique certainly ove

rlaps that of its sweep brethren, but success in a single requires additional skills. It’s possible to bury flawed technique in the middle of an eight, especially with vigorous power application and indefatigable endurance. Power can trump style in a bigger boat. Technique is power in a smaller one.

Developing a feel for rowing a single takes time, even for an Olympic sweep rower. Maneuvering such a slip of a shell requires a sensitive touch, but there’s no such thing as a delicate stroke. Pulling is pulling, regardless of the number of oars, but the margin of error for getting those oars in and out of the water declines with the decrease in seats. Initially, merely staying upright poses a challenge; flipping comes more naturally than pulling hard. No companion is present to counter a bad stroke or to smooth the rough edges of choppy technique. It’s all you, babe, for better or worse. There’s no one to blame or hide behind, no one to defer to or direct.

The first morning of development camp, Tom organized the accumulated rowers into pairs, as doubles provide a more stable base for practicing sculling technique than singles. He sized me up and matched me with Ann Strayer, who was my height, give or take an inch, another shrimp in a salmon’s world. We were roughly the same build, too, although her arms were bigger and my legs were stronger. Perhaps Tom thought our physical similarities would translate into symmetry on the water.

“Oh goody, fresh blood. I get to row with the latecomer,” she said.

I rolled my eyes.

“Seriously,” Strayer said as she held out her hand to shake, smiling. “You come with a reputation. I’m looking forward to this.”

She hailed from the Ivy League, too, a senior at Princeton University, land of the exclusive eating club scene, but Ann Strayer couldn’t even pretend to be snooty. Cheerful and energetic, she reminded me of a playful puppy, eager for attention and adept at getting it.

Synergy kicked into action that morning when we stepped into a double together. Our bodies clicked into sync right away. We were about the same length through the water, which helped our blades exit the water simultaneously. Our body angles at the catch and the lengths of our reach—the angles created as we extended our hands to drop our oars into the water—also matched. These details set up optimum conditions for an effective drive.

Tom was right. We were a good match. After that first morning practice, he kept us together the entire week instead of rotating us among other partners. Strayer stroked and I followed: a good thing, because otherwise she’d have talked nonstop. Only the wind could catch her words from the stroke seat, unless she turned around, which was too disruptive to her rowing motion and the boat’s balance. She had no choice but to concentrate.

She was easy to follow. No jerk in her stroke, a smooth body motion without any hitches, clean blade work, and consistent pacing. And she was sufficiently sure of her competence to qualify for the stroke seat. I was content to follow and steer, to match her technique and punch it up with my aggressiveness.

Our personalities meshed well, too, but not because they matched. She was happy-go-lucky, fun loving, and ready to joke, but sometimes had to be reminded to buckle down and get to work. She shoved worry on the back burner and spent no time considering potential obstacles.

It wasn’t that she couldn’t be serious. Of course she could be. But she approached life almost wide eyed, ready to be entertained and amused. Self-protection was not her concern. The future would sort itself out. Her job was to find the fun in the present.

Following Strayer brought me into the moment, dragged me away from my apprehensions; feeling me behind her, muscling the boat with intense purpose, in turn inspired her to bring her focus in and concentrate on the goings-on within our boat. I lured her in, and she tempted me out. Together we created a present with room enough for us both.

By the end of the week, we knew that our double had world-class potential written in bold ink. We were destined for greatness. Actually, Strayer said that; she could make those kinds of assertions without swaggering, but with genuine amazement at us and our promise as a fast boat.

I knew something different. Yes, we could be fast, and I could be in trouble. I was enjoying myself far too much.

Our camp coach was a master of the finer points of sculling technique. Tom described minute details of body position and rowing motion as a painter might describe hand position and brush strokes. We were artists in training, pursuing the perfection of rowing, steeping in the finest technical points, imprinting our learning with deliberate accuracy on the cellular level.

He sat patiently on the end of the dock beside Strayer, who balanced in a single beside him. He talked to her quietly, almost reverently, painting a picture of the perfect stroke. She sat with an oar loose in her hand, listening to the sound of the blade meeting the water as she dropped it in. Close your eyes. Feel the motion of the oar backing in, a little bit of backsplash, but not enough to disrupt the water too much. That will slow the entry. You want to feel the instant where the blade backs in and starts going forward. Hear what that sounds like. Try again.

The Southern California summer sun beat down. The water lapped gently against the dock. Her hand moved a few inches toward the stern, up into the catch. She noticed where her hand traveled, how it changed direction and affected the blade at the other end of the oar. Do it again. She sensed the linkup traverse her arm and connect with her upper back muscles. Again. She felt the relaxed grip of her fingers contrast with the contraction of those muscles as they engaged to start the stroke.

I watched her at the dock with Tom. I sat beside her on the grass outside the dorms of UC Irvine. I listened to her voice, the lilt of her questions, the laugh that gurgled beneath her words, suppressed sometimes in serious conversation, flashing to the surface again when she returned to sunny subjects. Her disarming honesty coaxed down my barriers. We traded our stories of growing up and filled in the details of our family histories as we sketched the start of our relationship.

Close your eyes. Feel the motion of the conversation, heading into unguarded waters. You don’t want to disrupt the course of this budding friendship. That will derail it. You have already missed the instant when your casual interest shifted into desire. You want to feel this transition as you keep moving forward, as the intensity ramps up. Hear what falling in love sounds like; the sunshine in her laugh, the catch in her breath during power tens, her voice reaching for me, a heat-seeking missile, dead-on accurate.

My thoughts lapped up against my heart’s wants. Strayer brushed her hair out of her eyes, and my hand wanted to follow hers, smooth the hair, and brush the down on her cheek. Try to focus again. My entire body on alert, heart beating, thoughts fluttering, blood rushing. Again. I imagined taking her hand in mine, feeling the taper of her fingers, the contrast of her calluses with the softness of her inside wrist.

Strayer captivated me. I could listen to her talk about almost anything. And I was on fire around her. It became progressively harder to restrain myself from touching her, to stop myself from inventing excuses to rub up against her warmth or accidentally stroke her skin. Her biceps looked juicy, a standing invitation to fondle and squeeze. Whenever she touched me—her hand on my foot when she turned to talk to me in the boat, her fingers grasping my shoulder to get my attention, the friendly hug she enveloped me in to say hello—I felt her energy zap through me. I had to steel myself to keep from grabbing her.

“Hey, I bought some gifts for everyone,” Strayer said on our last afternoon practice of the camp. We’d have one more the next morning. Then good-bye.

She held the bag out toward me. “I thought I’d hand them out at practice.”

I peered inside at an assortment of pastel-colored, handgun-sized water pistols made of cheap hard plastic with little rubber stoppers.

“Are you kidding? What makes you think Tom’s going to go with this?”

“Really? I think he’ll enjoy a break from our routine.” She grabbed the bag back, dug her hand inside, and pulled one out. “This one’s for you. You

can fill it up before we launch.”

Tom grinned when Strayer presented him with his very own water gun. He tucked it into his waistband. “No shooting the coach,” he instructed.

We launched with the standing shove Strayer had taught me earlier in the week, a move that requires more dexterity than I would dare attempt solo. With her instruction and encouragement, I’d taken the plunge. Standing with one foot on the boat’s floorboard, right between the seat tracks, I placed my other foot on the dock, avoiding the riggers. Holding the handles of both oars in one hand, and using my landlubber foot, I pushed the boat off from the dock in time with Strayer’s foot shove. Now waterborne, we both slowly brought our free feet into the boat and sat down on our seats without jarring the boat or falling into the water.

“Hey, Gilder,” Tom called as he motored up in his launch.

I said, “Strayer, get your gun!” We grabbed our loaded water pistols and cocked them toward our coach, but he was too quick for us. His camera was loaded and he had already started clicking pictures, admonishing, “Don’t shoot the coach.”

By then we had spent nine days together, attending double practices that, although technically demanding, were not physically challenging. We had had lots of time to break down the discrete parts of a rowing stroke and study their details. We’d had ample opportunity to tell our life stories and learn the ins and outs of each other’s personalities. Our canvas had the broad strokes of our future outlined.

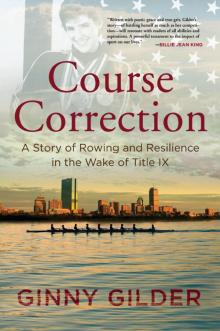

Course Correction

Course Correction