- Home

- Ginny Gilder

Course Correction Page 11

Course Correction Read online

Page 11

None of us ever lived with my mother again, but the days immediately following the midnight rescue tore my insides like tissue paper. I often stood by the living room window looking across the low roofs of the brownstones that separated my new home from my old one. I had a clear view through the back windows of the old penthouse apartment into Peggy’s room, the gym, and the laundry room. I scoured the rooms for signs of my mother. I never saw her. But I didn’t have to see her to know what was happening in that cavernous apartment. I couldn’t stop thinking about her. She was all alone now. I worried about who would wake her up to start the day; she had little if any reason to get up. Without anyone to care for her, would she disappear?

7

All eights are crews, but a mighty eight can become a sisterhood. You learn each other’s strengths and weaknesses. You coax out each other’s self-confidence, confront and overcome obstacles together, challenge and compete with each other. It is often messy. Not everyone likes each other. You put each other down. You pull each other up. You gossip, argue and debate, needle and incite, protect and cover for each other. You develop trust and earn respect. Nine women combine in myriad ways to develop connections, consistent with their own styles and personalities. The result is a synergy composed of a pattern unique to you.

When you get in the boat and shove off from the dock, you know what matters: everyone is prepared to do whatever it takes to cross that finish line first.

Chris Ernst never raced with us again, but she sowed the seeds of the sisterhood that became the unstoppable Yale Women’s Crew of 1979, three years after she lost her last college race. The day of her outburst, our crew’s bond was thin, a handful of strands not yet wound together in a purposeful pattern. We had struggled individually through winter training, but we had not suffered together as a crew. We had not felt the sting of losing. We had not gagged on the stink of defeat. We’d not had to confront each other eye to eye and acknowledge we’d let each other down.

There is no way to learn how bad losing is, except by doing it. Unfortunately, you have to develop a personal and deeply familiar relationship with failure to become great at anything. Losing is the most effective way to inspire improvement and generate success. It paints the gap between dreams and reality in brilliant colors. It reminds you of what’s important and why you care.

If you listen carefully, you can hear its whispered call, promising better fortunes if you recommit yourself, put your head down, and get to work. Or you can give up and go home. Your choice.

As I stood on the Gales Ferry dock while Chris berated our bedraggled and tremulous group of freshmen, I couldn’t see the future; nor could she. Blinded by disappointment’s glare, Chris blamed us for a trite truth: a crew is only as strong as its weakest link. Our eight was young and inexperienced. She was right.

Nine months of rowing was too short to learn to pull at full power for an entire race. It was not enough time for me to learn how to use my body optimally; to realize that I could pull for my teammates in front or behind me, even if I couldn’t muster the belief to pull for myself; and, finally, to discover I deserved to win as much as the next person.

I had to learn that as much as losing sucked, it was as necessary to success as stairs and circuits. Without it, I would never discover the power of my own will.

By the time my class graduated, we had lost only two dual races over my four seasons, including that loss to Radcliffe freshman year. We won the Eastern Sprints twice and would have made it three times if gale force winds hadn’t canceled the regatta my junior year. We won the Collegiate National Championships as seniors in the twilight of our shared competitive careers. We established the standard by which subsequent Yale women’s crews would measure themselves for nearly thirty years. But that day, all I knew was that all the hard work, hours in the weight room, tank sessions, and stairwells hadn’t paid off. Our season had ended shrouded in disappointment and sorrow.

What was to love about this?

The question followed me home from Gales Ferry and plagued me in the early weeks of summer, while Chris and Anne tried out for the Olympic team and ended up in Montreal as members of the first US women’s Olympic rowing squad. Then I watched the US women’s eight claim the bronze. I saw myself reflected in the late-night glare of the television set, standing tall on the victory platform, hands raised above my head, a medal around my neck.

I didn’t take long to decide. Losing sucked, but rowing wasn’t the problem. The problem lay elsewhere: lack of preparation. I knew from way back that the best defense was a good offense. Be strong, tough, unstoppable. Be prepared for anything, because disaster could strike from anywhere. Training was the answer.

Late August rolled around. I couldn’t wait to return to the boathouse, greet my teammates, and step into a racing shell again. I yearned for the view from the water, the peaceful scenery balancing the energy within the boat. I ached to belong again. Captain Chris wouldn’t lead our team anymore, but we’d learned so much from her. We’d figure it out.

But I had something else to figure out too: how to go about training for the Olympics.

I didn’t know whom I could ask for advice or whom I could trust with my secret. My coach? Nat would pop my bubble as soon as I shared it. He’d say I was a young and inexperienced rower on a pretty fast crew. He’d warn me not to get my hopes up. He’d quietly doubt my potential, as he had from the moment he met me. He’d privately think I was nothing special.

Anne Warner? She’d listen all right, but I guessed what would follow: an incessant drive to show me how far out of her league I was.

Captain Chris? She had retired as captain upon graduation, but returned to the program as Yale’s first women’s novice rowing coach. I more than looked up to her; her confidence and forceful personality dazzled me. She had concentrated intensity that I had never experienced and a no-holds-barred willingness to kick anyone in the ass who tried to stand in her way, and was fearless in the face of authority and comfortable positioned out of the mainstream.

Heck, even being gay didn’t make her hate or doubt herself. Chris didn’t broadcast her sexuality, but her utter disinterest in guys, to the point of disdain, was obvious, although, in fairness I only saw her around the heavyweight guys, and they deserved disdain. She was the first out lesbian I had ever met, and her refusal to hide or apologize fascinated me.

I couldn’t imagine being that bold or comfortable about an aspect of myself that much of the world, especially my world, with my father topping the list, condemned as deficient, if not depraved. I admired her matter-of-factness about who she was and her contempt for anyone who judged her harshly. I longed to be like her: that self-confident, that assertive, and that impervious to the opinions of others.

The mid-1970s were early times in the gay rights movement, with the Stonewall riots that served to catalyze the shift from a more conservative, less aggressive movement to one that was clearly out and proud less than a decade past. On campus, I didn’t see any evidence of the movement, nor was there much discussion about homosexuality, although I wasn’t looking or listening for any. In the small pond that comprised the Yale Women’s Crew, everyone revered Chris, gay or not. If anything, her sexuality made her even more of a standout and more of a leader, as she modeled self-confidence and assertiveness in pursuing her goals without allowing the opinions of others, either individuals or society as a whole, to interfere with her dreams.

Maybe Chris would understand my impossible dream, my secret longing. Maybe she’d support my boldness, if nothing else. But memories of our last contact on the dock at Gales Ferry still stung and brought me back to earth.

Besides, no matter to whom I confessed my dream—Nat, Anne Warner, or Chris—they would all be right. I was crazy to want it. I knew that from the start. But the heart wants what the heart wants.

Sophomore year began. I sewed my first varsity letter, a big, dark navy Y made of felt, onto the traditional soft white letter sweater with its boat collar that

had trademarked Yale varsity athletes for over one hundred years. Sewing and sports existed at near-opposite ends of the femininity spectrum, a span I didn’t ponder as I wielded my needle. I was stitching myself into the role of pioneer, as I attached the flimsy felt to the chest of my sweater, my own personal story just one thin thread tugging at the fabric of American culture, helping to reconfigure the still-prevalent view that women’s and girls’ engagement in athletics posed a threat to their health and femininity.

I just wanted to wear my letter sweater proudly, but history had to play out in its own time to reverse the backslide in cultural norms. By the early twentieth century, most women’s colleges and a smattering of co-ed schools offered instruction and competition in several sports, including archery, baseball, basketball, rowing, tennis, and track, but in the mid-1920s, a cultural rebellion against the concept of the “independent woman” slowed progress. Bearing in mind that this era birthed the Miss America pageant, the concerns that engagement in sports promoted “mannish” characteristics and produced women who would be too strong and unable to submit to their husbands’ authority fit with the times. For the next four decades, educators and parents viewed female involvement in competitive sports as both a health and a moral hazard; women’s colleges across the country downgraded their competitive intercollegiate offerings to intramural status, focusing on socializing and fun, not winning.

Few statistics documented women’s involvement in sports; “ladylike” sports—badminton, golf, swimming, and tennis—were encouraged at the expense of more active team sports, like volleyball, basketball, and softball. Women’s track events were limited to distances no greater than two hundred meters in competition. Avery Brundage, an American and the president of the International Olympic Committee, actually advocated reducing the number of women’s track events in the Olympics to remove the less feminine ones, like shot put and distance running.

The arrival of coeducation to the Ivy League thankfully coincided with changing attitudes about women’s involvement in sports, as the passage of Title IX demonstrated. Still, I didn’t realize that official Ivy League competition in women’s sports had started only a year before I ripped open my acceptance letter from Yale. In fact, the first championship awarded was in the sport of rowing. And with admissions departments debating whether to confer the same priority to women athletes granted to men, the death knell of the myth that sports harm women was beginning to sound.

I quickly settled back into campus life. No longer a freshman, my Old Campus days behind me, I moved into my residential college, Branford (where my father had lived, too). I shared a triple with Ruth and Sandy, two classmates I had lived across the hall from freshman year, who were acquaintances more than friends. We shared no interests, classes, or friends, and rarely gossiped, shared meals, or hung out. Our first week of school, we bought two-by-fours and plywood and constructed a third bedroom out of the living room so we could each enjoy the privacy of our own room.

Located at the top of the narrow tower situated on the west corner of Branford’s dining hall, our suite took up the entire floor, as did the ones on the two floors below us. Only nine people lived in the tower, which meant our shared entry didn’t see much action. That was fine by me. I loved the peace and quiet that came with being out of the fray, and the privacy, too. I could come and go as I pleased without having to satisfy anyone’s curiosity and could choose what to share with whom without interference or prodding.

I allowed myself to fall hard for a guy, an upperclassman who seemed to like me, too. Don was a svelte New Yorker, an indifferent athlete, but nicely built, articulate, and funny. He was two years into an extended recovery from the loss of his first love, and I was glad to help ease his pain, not realizing that he had decided to keep his distance when it came to romance. Misinterpreting his casual interest for something more substantial, I spent my share of nights with Don at his off-campus apartment, enjoying our physical intimacy and loving the sense of emotional security with which I imbued our relationship.

I landed with a bad bump when he dumped me at the start of second semester, and although Don had introduced me to some fellow Branford students whom I liked, I withdrew from those budding friendships to save myself the humiliation of public mourning. Instead, I took most of the spring to recover and vowed that love was not for me.

But I did find one new friend in the process. David had also fallen for Don when they met their freshman year, but settled for friendship when Don defined the strict boundaries of their relationship. Don was not bisexual, so David had to settle for one-sided flirting and platonic dinners filled with banter about English literature and foreign movies. I appreciated David’s biting, sarcastic sense of humor, and his self-deprecation about his situation with Don. We ate our share of meals together, trading tidbits about the guy we had in common, and when Don finally gave me the heave, David was there to comfort me.

Meanwhile, my father and I debated my major. I loved math and was drawn to computer science, but he suggested a novel approach: “Do something that’s hard for you, that you’re not so good at.” My memories of the red C minuses my freshman English professor had scrawled across the bottom of my papers, along with the oft-appearing directive “see me,” floated at the periphery of my father’s counterintuitive advice. A major in English would require lots of writing, but no senior essay. That seemed too easy, so I searched for another major with a heavy writing requirement and a senior essay. History fit the bill, so off I went.

But, really, I majored in rowing. I chose my courses according to its seasons and arranged my classes around practices. I worked out with my teammates and followed Anne Warner’s lead without fessing up to any goals beyond gold for the Bulldogs. She’d returned from the Olympics with a bronze medal, but was bitter toward us, as her haughty attitude the previous year had resulted in the large group of irreverent freshmen (five of us who’d rowed with her in the varsity) electing as captain not her, but a top lightweight instead.

Bakehead, who had rowed the previous season in the six seat, was musing about trying out for the 1977 National Team. Anne Boucher (Bouche) had also joined us—our program’s first-ever experienced freshman recruit. She came with an illustrious high-school-rowing pedigree and an open interest in climbing the highest rungs of the sport. I could stay safely under the radar and stealthily pursue my private fantasies without having to expose myself at all.

There was only one problem. Okay, maybe not only one, but this one blindsided me.

It shouldn’t have, because my asthma had been a fact of life since sixth grade. Back then, a visit to the doctor diagnosed the condition, but in my hardheaded, defiant twelve-year-old way, I decided the guy was wrong.

After all, he claimed his specialty was ears, eyes, noses, and throats, and my problem lay south of my neck, by my estimation well below his geographic expertise. Plus, I couldn’t understand how something could be wrong with me when everyone else in my family was A-OK. They all could breathe just fine. After all, we shared the same genes. To top it all off, he blamed my cats for making me sick. Those sleek, dark-brown companions with long, wavy tails—our pair of Burmese, Chocolate and Vanilla, were my biggest fans. They showed up at the front door every afternoon when I returned from school and followed me everywhere until bedtime. I had slept with them nightly for eons, surrounded and protected. There was no way my cats were the problem.

The facts, however, were hard to dispute. My skin broke out in itchy blotches wherever Chocolate rubbed against me. Accidental scratches turned into jagged red lightning bolts and then swelled into angry welts. Sometimes when he slept snuggled up beside me on my pillow, I felt as if something was hugging me to death from the inside, squeezing all the air out of my lungs. I couldn’t figure out how to grab hold of it, shake it loose, and throw it out of there.

In addition to cats, several other life essentials found their way onto the list of dangers: dogs, horses, hay, grass, chocolate, dust. Show me a place on earth wit

hout dust. I couldn’t go anywhere without being threatened by my environment.

Part of my punishment required trekking to Midtown every Thursday in the middle of the school day for shots designed to desensitize me to the allergens that the experts insisted triggered my asthma. No one picked me up or accompanied me. My mom and her constant companions, Mr. and Mrs. Marlboro Lights (she had dumped Mr. Lucky Strikes for filtered cigarettes because they were supposedly safer), couldn’t muster much sympathy. She kept the windows closed in my bedroom because the doctor insisted that cold air was tough on my breathing, and she sat me in the smoking section when we went to the movies. She insisted I take my medication, which zapped my pulse into the stratosphere like a jittery rocket and made me sick to my stomach, but her aversion to vomit meant I had to throw up alone, curled up on the bathroom floor, clutching the sides of the toilet as the waves of nausea gradually receded.

I’d been taught by experts to stuff my problems into silence. Maybe my body had taken the lessons to heart. Maybe this was payback: no more room down there, not even for oxygen.

My departure for boarding school in tenth grade had improved my health. Dana Hall was in Wellesley, Massachusetts, just outside Boston, where the air was cleaner, my bedroom was free of cat hair, and I was far away from my family drama. I had lived with my father, stepmother, and three siblings for less than a year when I fled to Dana Hall, desperate to escape the tension of living in a household dominated by a woman who continued to repeat that she never wanted children and didn’t care for the ones under her roof. Constant arguing and putdowns by BG wore me down, especially because my father almost always took her side. No matter what I did, excelled or under-performed, BG was never satisfied. To counter BG’s success in swaying my father’s opinion, I welcomed solo time with him. Nonetheless, for a former star goody-goody, my change in status to bad-attitude girl felt crushing.

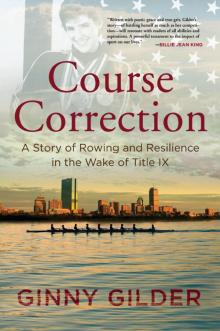

Course Correction

Course Correction